Behind the book: Adventure at the bottom of the world

"Writing this book was extremely difficult." How Elizabeth Rush mixed memoir with 213 interviews on a scientific expedition to Antarctica.

It sounds like the premise of a Michael Crichton thriller: Four years ago, 57 scientists embarked on a sea voyage to an Antarctic glacier that had never been explored before. Their mission: To learn as much as possible about the environment before climate change destroys it completely.

But this isn’t a work of fiction — it really happened, and the Pulitzer finalist journalist Elizabeth Rush was embedded among the group to document their lives at the bottom of the world, from “a ping-pong tournament at sea” to “all the effort that goes into caring for and protecting human life in a place that is inhospitable to it.”

In The Quickening (August 15, Milkweed Editions), Elizabeth also explores the underreported role of women and people of color in scientific voyages, as well as one of the most pressing questions of our generation: “What does it mean to bring a child into the world at this time of radical change?”

It’s a gorgeous and fascinating mix of on-the-ground reportage (well, on-the-sea-and-ice reportage) and memoir. In this week’s Behind the Book, I was thrilled to speak with Elizabeth, her editor Joey McGarvey (now at Speigel & Grau), and her cover designer Mary Austin Speaker about making The Quickening.

Elizabeth Rush (author)

When and how did The Quickening begin for you?

My engagement with this topic has many beginnings. I had been writing about climate change's early impacts on coastal communities for nearly a decade, and during that time I had grown comfortable with a certain level of uncertainty in the climate models. Will we have 3 feet of rise or 6 feet of rise by century's end? No one really knows.

But then I read an article on Thwaites Glacier that made me uncomfortable again. In essence it said that many of our climate models (at the time) didn't take Thwaites and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet into account because we have next to no observational data from this place. Thwaites could be a real game changer in terms of the possibility of accelerated sea level rise this century and beyond but because we had no way of cataloging its behavior we had no way to reliably include it in our projects of the future.

So I decided to apply for a grant through the National Science Foundation that sends artists and writers to the ice and I was very fortunate to be offered the last berth on the R/V Nathaniel B. Palmer—the first boat to ever reach Thwaites' calving edge. That is one starting place.

This narrative also starts in the library. As I began to learn about Antarctica I quickly realized that the first person to see the last continent did so in 1820; which means that all of our first-hand accounts of the ice have been penned during the last two hundred years. When you think about what is happening in human history during this time it is not surprising that most of these stories are tales of imperial conquest, extraction, narrated by "exceptional" men sallying forth to achieve the unthinkable (or die trying). So I knew early on that whatever I would write would have to push against those traditions in its own way.

What was your research process like?

One way I decided to go about destabilizing the traditional explorer narrative was to commit to the idea that I would not be this book's sole narrator. I wanted my shipmates to narrate their journey towards Antarctica as well.

During the 54 days I was onboard the Palmer I maintained a really regular interview practice. I conducted between 3-5 interviews a day with my shipmates. I didn't just talk to the scientists; I also spoke to the cooks and crew onboard the boat. So often support staff is written out of the official accounts of Antarctic expeditions and so I wanted to create a record that included their experiences. I did 213 interviews while onboard and I hand transcribed them as well during the mission. Honestly, that was the biggest lift in terms of researching this book, it was creating the archive from which it is composed.

What was the most difficult thing about writing this book?

I'm not going to lie, writing this book was extremely difficult. When I hold it in my hands today I almost can't believe that it exists. I wrote it almost entirely while pregnant and then as the mother to a newborn and later an infant.

My son was born in May of 2020, right in the very beginning of the pandemic. Not only was finding time to write difficult, it meant really leaning on my community to help me care for my son. My husband, his mother, my parents, my sister-in-law, Elvira Villamil (who has worked for my sister-in-law for decades), and Patty Rodrigues (who would become Nico's nanny) all took turns caring for Nico so that I could take time away to write. And even when I did find the time I often felt that my energies were zapped (before I even typed my first word) by sleeplessness and the sensation of having to constantly be vigilant against a threat we did not understand.

So, yeah, the whole thing was pretty hard. But this is a book about community and what is possible when you work with others and attempt to do the unthinkable. This book is a product of my community.

Along those lines, I would be remiss if I didn't mention [my editor] Joey here. I knew that writing this book was going to be tough (even without the pandemic) and I knew that I wanted Joey to be my traveling companion on this journey.

She and I had worked so well together on Rising. I knew I could trust her completely. I knew that she would ask the difficult questions without tempering the book's ambition. I also knew that she would be deeply involved in the line-editing. So whenever I wavered I was reminded that things would be okay because I had faith in Joey and our ability to collaborate and create something that we are both proud of. She really was an incredible guiding light and source of grounding throughout.

Joey McGarvey (editor at Milkweed Editions, now at Spiegel & Grau)

What drew you to The Quickening and to Elizabeth's writing in general?

The Quickening is the second book Elizabeth and I have worked on together—our editorial relationship has lasted almost a decade now. But I still remember my initial read of Rising, our first book together. For example, I remember encountering the powerful testimonial—one of the distinctive craft elements Elizabeth brings to her work is the incorporation of first-person accounts—from Nicole Montalto, a Hurricane Sandy survivor who lost her father in the flooding.

Elizabeth has a great ear for the music of other people’s language—the testimonials are heartbreaking, funny, illuminating. And of course there’s so much music and craft in her writing too. Elizabeth never lets herself off easy. She’s always pushing her writing to be as interesting and surprising as possible. That was all very present in The Quickening from the early stages. I was also excited to see what an adventure narrative might look like in Elizabeth’s hands, with what she could do on that canvas.

What made The Quickening a great fit for Milkweed?

During the writing and editing of Rising, I worried a little that the book, like any on climate change, would be outdated the moment it was published. But I’ve been thrilled, over the last five years, to watch it find a place in the canon of climate change literature. Because Elizabeth brings great empathy—and a determination to write about climate change in different, challenging ways—to her books, I believe readers will continue coming to them even as the transformation of our world continues. In short: Milkweed is lucky to count her among its authors, to include her contributions on its already strong list of nature writing.

I, personally, was lucky too. I moved on to a new position at the independent publisher Spiegel & Grau in November of last year, and Elizabeth and I just had enough time to finish our editorial work on The Quickening before my departure.

How did The Quickening evolve during the editing process?

I’m trying to think of what shifted and what we kept and what we didn’t keep. There was a lot of conversation about POV. Several earlier drafts were in the second person, before it moved to the first person. There are a few nods to dramatic forms—there’s a cast of characters, and some stage directions, and a multi-act structure. There was some discussion about that; we kept it.

The book got longer. There was a draft where there was very little about the return journey, and we decided to expand that more. We looked for more points of intersection and development between the two big stories of the book, of the journey to Antarctica and Elizabeth’s decision to have a child. And the title changed! For a long time, it was titled The Mother of All Things, but we changed it just as the manuscript was finalized.

Mary Austin Speaker (creative director at Milkweed Editions)

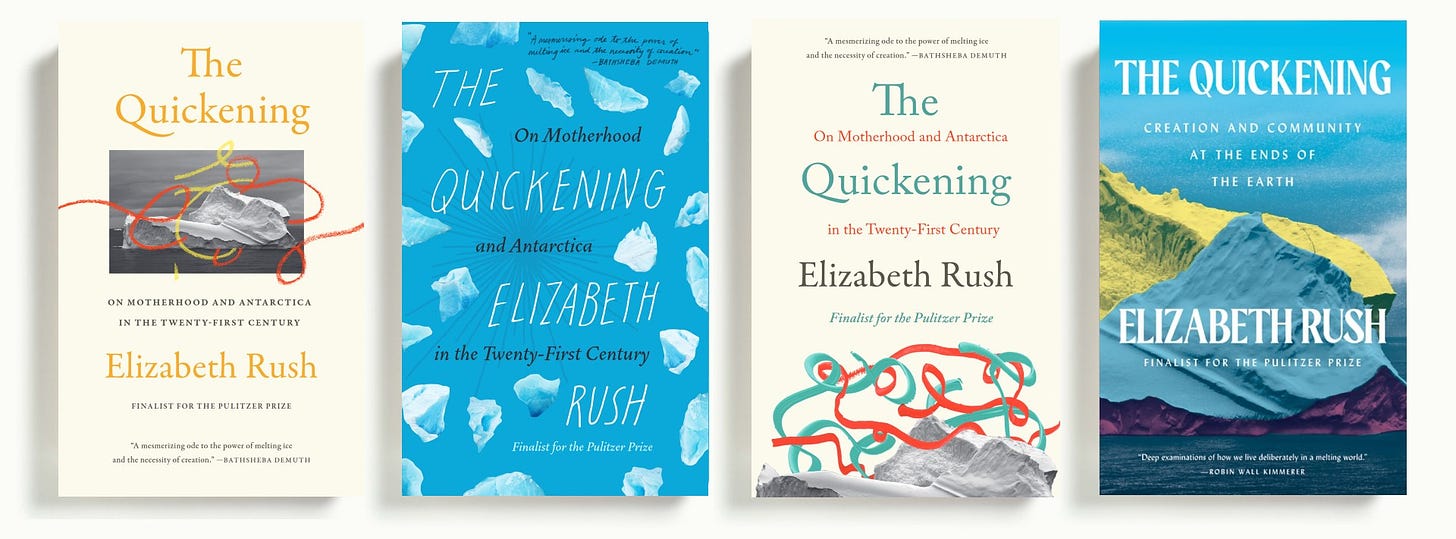

How did the cover design evolve over time?

Throughout the publication process, Liz was interested in giving this book the look of a novel. We wanted to highlight the polyvocal nature of the writing, so my suggestion was to superimpose an illustration (in this case a painting I made with a few different colors of acrylic markers) over a black-and-white photo of a glacier.

I was inspired by covers of novels, poetry collections, film festival posters, anything that indicated the threading together of multiple narratives. We were relying on a fairly conservative type treatment to lend the book an authoritative tone, with the illustration—hopefully— disrupting that a bit, but the design felt ultimately a bit confusing.

I also tried illustrating the ice breaking apart in order to signify the active melting of the arctic ice, with some hand-lettered type to signal the warmer, more human approach to the subject—but that, too, didn't get at the vibrancy of Liz's project, or its formal complexity.

Liz had suggested a treatment that mimicked the old hand-tinted tourist photographs from the turn of the 19th century into the 20th, which I happen to adore and collect. I loved this idea and how it held the potential to allude to Liz's dynamic, polyvocal take on a story traditionally told about one person— usually a man, but instead using design to indicate the collaborative, experimental nature of the book.

This iteration of the hand-tinted photograph would be vibrant and a little messy around the edges, geared toward expressing the feeling of amazement of being in that place as well as the many colors that ice allows you to see when isolated from everything else (which Liz describes so beautifully in the book). So I altered one of Liz's photographs to be black-and-white, brought up the contrast, and made some masks in bright colors to set over the photograph, the way designers from the 1960s would have created gel transparencies to emphasize particular areas of an image.

We wanted it to look antique, but a kind of ultra-vibrant mashup of vintage styles, blended together enough to look very contemporary. I selected a typeface with a 1980s look— not something you'd expect on an "authoritative" book but something more in line with what you might find on a novel— and that was by design, too. Ultimately we are very happy with how the package turned out— it's bright, engaging, and sends the signal that this is a new take on an old narrative— and one that has room for everyone.

Coming soon in The Frontlist

My September book preview and a Behind the Book with Lydia Kiesling.