Behind the book: Why AI *should* kill the student essay

John Warner on MORE THAN WORDS, reading, writing, and thinking in the ChatGPT era.

The explosion of ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot, and other consumer AI tools has impacted just about every profession on Earth — but perhaps none more so than writers. Tech companies, C-suites, publishers, and writing students around the world have become obsessed with the idea that software can do all your writing for you — an idea that’s already disrupted everything from web publishing to college classrooms.

In More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI, John Warner argues that AI “not only can kill the student essay but should, since these assignments don't challenge students to do the real work of writing.” It’s a timely and fascinating look at why teachers and administrators should embrace the fact that reading and “writing is thinking,” not something an LLM can do for you in a few clicks.

For The Frontlist, I spoke with John about his book, which pubs today. As “the Biblioracle,”

is a weekly columnist at the Chicago Tribune and writes the newsletter The Biblioracle Recommends. He’s also an affiliate faculty member at the College of Charleston and lives in Folly Beach, South Carolina.Can you share a photo of your writing space?

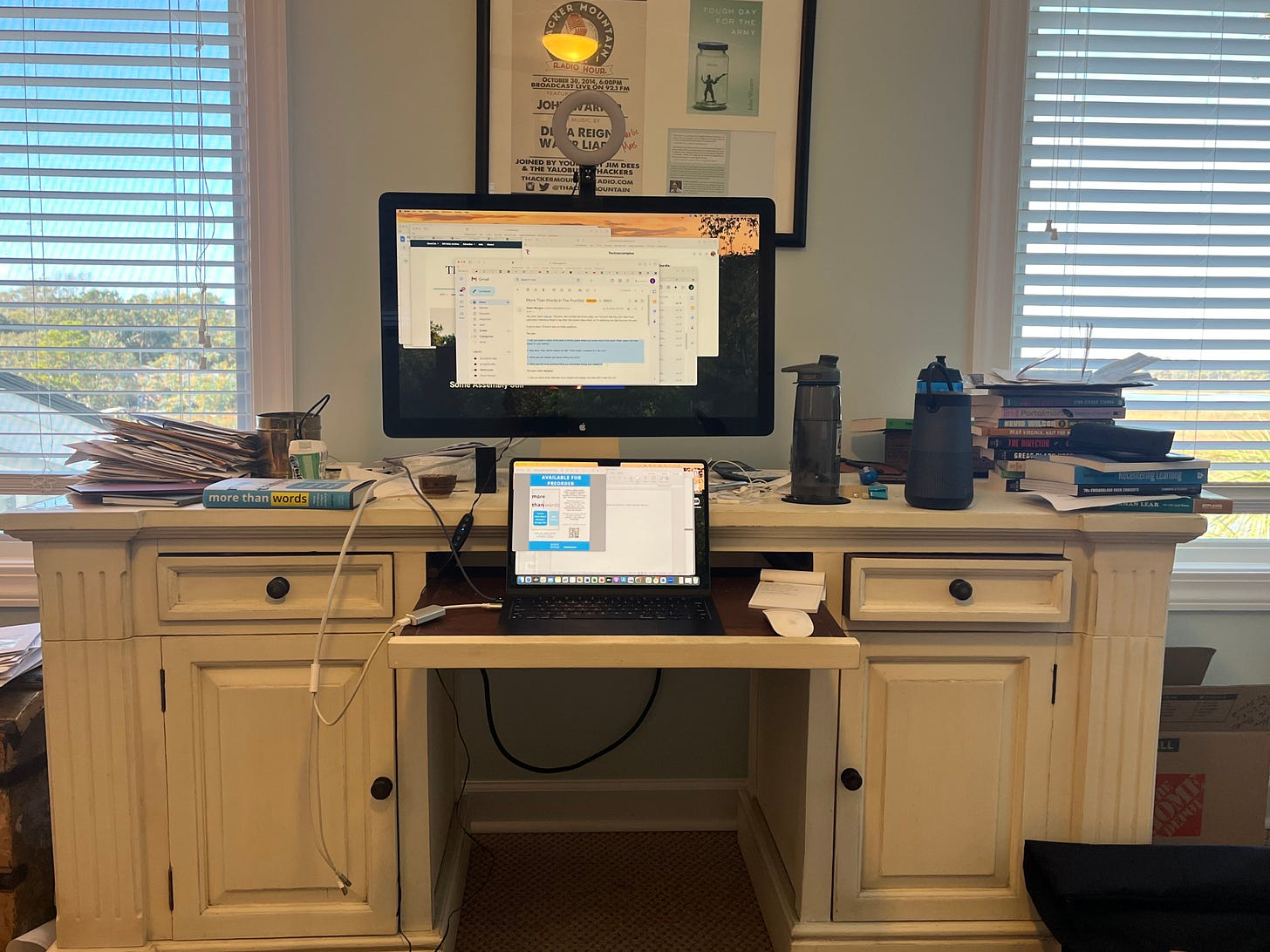

This is the desk in my home office, and I was sorely tempted to tidy things up for this feature, but why not just give into reality? Every couple of months I reset the surface to zero and get rid of all the loose paper, objects, unfiled mail, and move the TBR books somewhere more discretely out of sight, but this is a pretty good rendering of what the desk would've looked like while working on the book.

I am ashamed of the clutter, but this is simply the reality of what my workspace looks like when I'm in the midst of something, which is pretty much always. We've moved to this house with a view of a coastal salt marsh two and a half years ago, and the change I've enjoyed most is that my office is now a room with a view. I can look out and see the light change as the day moves along, and when the tide is up a group of kayakers may paddle by. All kinds of shore birds go swooping past. It's nice.

I like that the desk is big so I have places to put any materials I might be referencing and the large monitor where I can have both a full screen of a document page and an open browser is pretty much a necessity for book writing.

One of my consistent messages about writing in both this book and others is that writing is a "practice" and part of one's practice is the space and manner of how they go about their work. I don't know what this says about my practice other than it is definitely mine.

What was the most surprising thing you discovered during your research?

This is strange to say, but writing the book I was surprised to see how much more important my reading practice is to me than I'd truly appreciated. I think I'd come to take the fact that I can read in a myriad of different ways — skimming, deeply, like a writer, etc. — for granted.

Reading isn't a superpower since that conveys something that is rare or inaccessible, but it is the chief source of my agency in both work and life. It made me even more despairing about the ways reading has been reduced in school contexts and how students are often deprived of the pleasure of power of truly being able to read.

The fact that LLMs can summarize lots of text nearly instantly only makes reading critically, deeply, etc., more important, not less, but I fear that lots of folks are drawing the opposite conclusion. More Than Words is my attempt to say, "Let's hold on here!"

What was the hardest part about writing this book?

Given the nature of the topic, there was a bit of a time crunch to get it done as quickly as possible. I was worried about what I had to say being obviated by some kind of technological development. Making sure to stay reasonably on top of developments was important, and much of my mornings involved with reading that day's new news about generative AI and LLMs. There are gazillions of people with more expertise about those things than me, but I got increasingly proficient at taking in new information and seeing how it related to what I was trying to say.

Truth be told, over time, I became less worried about my message being obviated, as I realized that what I was writing was not primarily about shifting technology, but instead about enduring human processes.

The challenge then shifted, and I had to try to bring these processes of reading and writing to life in a way that illustrates their importance to the individuals doing those things. I was fortunate to have lots of years of teaching where I'd seen the shifts in student attitudes and orientations happen when they're truly turned on to the power of reading deeply and writing with intention, and I drew much more heavily on those experience than I initially anticipated.

Was More Than Words always the title? What made it a perfect fit in the end?

Is it the perfect title? I like the title, but titles are hard. The title on the original book proposal was Writing with Robots: Staying Human in the Time of Artificial Intelligence, which I knew from the beginning was a better title for a book proposal trying to interest publishers than the book I was ultimately going to write.

I don't remember what other titles were knocked around between my editor and I, but I think when More Than Words came up it felt good. It captures the key sentiment of the book, that there are important differences between the syntax generation of large language models and what happens when people read and write. The initial awe triggered by the appearance of ChatGPT has, I think, obscured this reality.

Or maybe it's that the ways we've allowed what is now a couple of generations of students to become alienated from the deep challenges and pleasures of reading and writing that have obscured this reality. Either way, it's something I want to reawaken in the audience.

I also like the subtitle "how to think about writing in the age of AI," because I intend the book to demonstrate my thinking as an inducement for others to do their own thinking. It's an example, not a prescription.

My only worry was that every time readers of a certain generation — the generation I belong to — saw the title, they would not be able to get this song out of their heads.

Preorder my book?

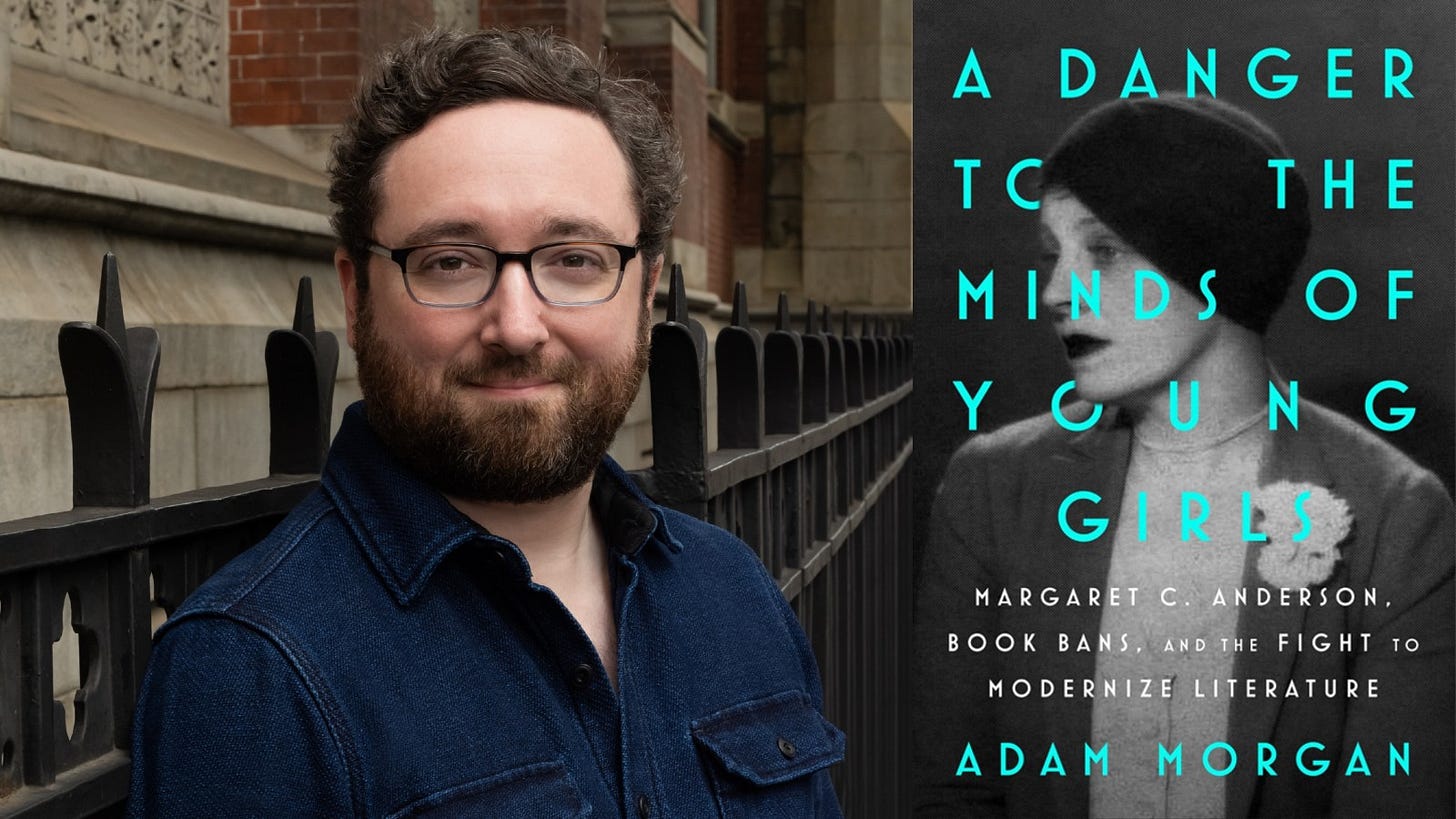

A Danger to the Minds of Young Girls: Margaret C. Anderson, Book Bans, and the Fight to Modernize Literature is now available to preorder if that’s something you’d like to do! Here’s what One Signal / Atria Books has to say about it:

Already under fire for publishing the literary avant-garde into a world not ready for it, Margaret C. Anderson’s cutting-edge magazine The Little Review was a bastion of progressive politics and boundary-pushing writing from then-unknowns like T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, William Butler Yeats, and Djuna Barnes. And as its publisher, Anderson was a target. From Chicago to New York and Paris, this fearless agitator helmed a woman-led publication that pushed American culture forward and challenged the sensibilities of early 20th century Americans dismayed by its salacious writing and advocacy for supposed extremism like women’s suffrage, access to birth control, and LBGTQ rights.”

But then it went too far. In 1921, Anderson found herself on trial and labeled “a danger to the minds of young girls” by a government seeking to shut her down. Guilty of having serialized James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses in her magazine, Anderson was now not just a publisher but also a scapegoat for regressives seeking to impose their will on a world on the brink of modernization.

Author, journalist, and literary critic Adam Morgan brings Anderson and her journal to life anew in A Danger to the Minds of Young Girls, capturing a moment of cultural acceleration and backlash all too familiar today while shining light on an unsung heroine of American arts and letters. Bringing a fresh eye to a woman and a movement misunderstood in their time, this biography highlights a feminist counterculture that audaciously pushed for more during a time of extreme social conservatism and changed the face of American literature and culture forever.